Larry Temkin

Being Good in a World of Need

Peter E Gordon

Migrants in the Profane

Janek Wasserman

The Marginal Revolutionaries

Michael Lewis

The Fifth Risk

Brooke Harrington

Capital without Borders

Jo Wolff

Ethics and Public Policy

Daniel Halliday

The Inheritance of Wealth:

Justice, equality, and the

right to bequeath

Martin Jay

Reason after Its Eclipse: On Late Critical Theory

Lesley Sherratt

Can Microfinance Work?

Boudewijn de Bruin

Ethics and the Financial Crisis: Why Incompetence is Worse than Greed

Nicholas Morris &

David Vines

Capital Failure: Rebuilding Trust in Financial Services

Looking at Warhol's Flowers

Jeremy Worman

Swimming With Diana Dors

Michael Ignatieff

Fire and Ashes: Success and

Failure in Politics

Jon Elster

Securities Against Misrule

Jesse Norman

Edmund Burke: Philosopher, Politician, Prophet

Michael Sandel

What Money Can't Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets

Hilary Mantel

Bring up the Bodies

Philip Coggan

Paper Promises: Money, Debt and the New World Order

Jeffrey Friedman &

Wladimir Kraus

Engineering the Financial Crisis: Systemic Risk and the Failure of Regulation

Jeremy Worman

Fragmented

Martin Gayford

Man with a Blue Scarf

Raghuram Rajan

Fault Lines

Jonathan Israel

A Revolution of the Mind

T.J.Clark

The Sight of Death

Beautiful Facts:

Recent Paintings by

Alison Turnbull

Jacqueline Novogratz

The Blue Sweater

Matthew Bishop &

Michael Green

Philanthrocapitalism

Camilla Howalt

James Griffin

On Human Rights

Ronald Cohen

The Second Bounce of the Ball

Edward Craig

The Mind of God and the Works of Man

|

You are an artist, are you not, Mr Dedalus? said the dean, glancing up and blinking his pale eyes. The object of the artist is the creation of the beautiful. What is beautiful is another question.

James Joyce, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

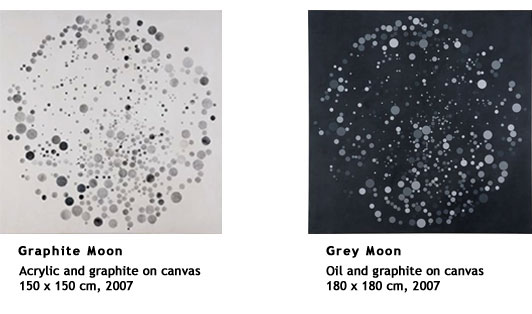

Two pictures: both are comprised of numerous small circles of varying size and shade of grey. These small circles combine together to form large, circular objects that fill the entire canvas. Despite the absence of defined borders or outlines both of these pictures are immediately seen to be large circles, each made from a variety of smaller grey picture elements.

The first picture has a light background and the degree of prominence of the small circles is determined first by the darkness of the grey and second by the size of their diameters. A cluster of pale grey circles just below the centre of the picture competes for attention with a loose configuration of larger, darker circles in the lower left. Small spots of dark grey are clearly visible throughout the image.

The second picture has a dark background and the circles form spots of light with gradations of brightness. In this case it is the pale grey circles that are more prominent. The viewer's eye is drawn both to a small cluster of bright grey circles at the top of the picture and then to a larger group in the lower right quadrant. In this picture the dark grey circles fade into the dark obscurity of the background.

Both pictures are striking: first, because of the obvious care and technical precision that has gone into making them; and second, because although they are both busy with content, they convey a mood of tranquillity.

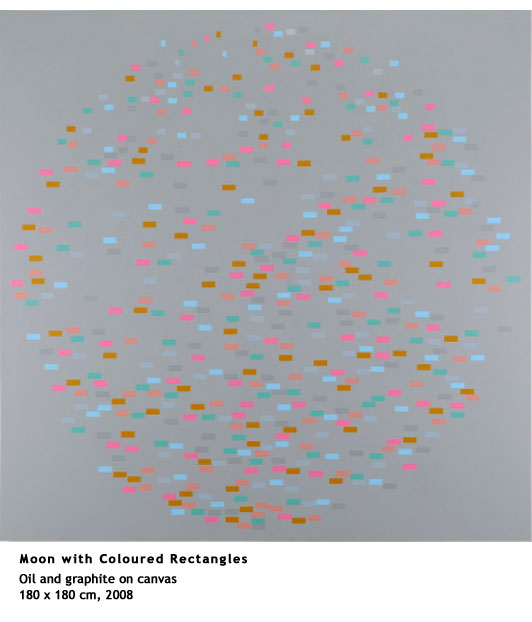

A third picture: in this case the grey background is covered by hundreds of small rectangles in a variety of colours including: pale blue, emerald green, yellow ochre, hot and pale pink, and light and dark grey. The rectangles come in three sizes: nine are small, ninety are of medium size, and several hundred are large. The smallest rectangles occupy slightly more than two square centimetres of canvas while the largest rectangles occupy fewer than seven. The entire canvas is 32,400 square centimetres in size.

Despite the use of angular rather than circular elements and a number of contrasting colours rather than shades of one colour, as before the circular form of the large image is instantly available to the viewer. The effect is striking and beautiful: this is another harmonious sphere.

These three paintings by Alison Turnbull are beautiful made-objects. They are large paintings, full of details that draw the viewer towards the canvas. The combinations of circles and rectangles create a variety of contrasts of shade and colour. There are clusters of intense activity and areas of sparse detail; there is order without regimentation. In each case the main image appears balanced, but without obvious artifice.

The picture titles confirm the images as faces of a full moon: familiar to all of us but, save for a privileged few, distant and remote. The moon's surface is covered with craters, the residue of extinct volcanoes or visiting asteroids. These pictures are covered with symbolic craters, painted marks that reinterpret the lunar landscape.

...

Maps are tools. They are representations of reality in which selected information is recorded using some consistent method of translation, thereby retaining its inherent interest or value.

On a traveller's map a road may be marked as blue, red or yellow. Not because the road itself is painted blue, red or yellow, for the colour of the road is information that the traveller is presumed not to care about. The colour marked on the map is important to the traveller, because it tells of the degree of importance of the road, its size, likely state of repair, and the speed at which the traveller might expect to be able to proceed along it.

Turnbull's paintings are not maps. She was not commissioned by NASA to manufacture tools that would enable astronauts to navigate across the surface of the moon. Rather she has taken information about reality and translated it just as a mapmaker does; but in her case the purpose and the result of the translation process is not utility but beauty.

Which pieces of information should be retained and which discarded? Which colours will be used to represent which objects? How will shapes and sizes be re-scaled? How will the balance of the final image be obtained from the picture elements of which it is comprised? These decisions, and the skill with which they are then executed, determine the quality of the painting.

Her depiction of the moon's surface makes no claim to be an accurate representation, but it is anchored in genuine astrography. The lunar facts have been simplified and re-scaled, but they remain integral. Her paintings capture the principal physical features of the moonscape and then re-order them with colour, shade and shape to re-present them as beautiful facts.

...

Alison Turnbull lives and works in London, which was also home, four hundred years ago, to Thomas Harriot: mathematician, scientist and astronomer. On 26th July 1609 Harriot made a sketch of the moon, the earliest known drawing of an astronomical object viewed though a telescope. Over the next four years he continued to study the moon and recorded his observations, making two maps of the whole of the lunar surface, with the major craters located in their correct positions relative to one another.

Thomas Harriot made hand drawn maps based on direct observation of the moon: nature was his source. By contrast Turnbull's sources are themselves made-objects, derivative products such as maps, drawings, pictures, plans and diagrams. All of these have intrinsic interest; they were made for a purpose and they convey useful information.

In the past she has worked with architectural plans of buildings, including houses, hospitals and industrial buildings that would not normally be deemed worthy objects of artistic representation. She has made use of floor plans for rooms in Japanese homes; she has used genealogical maps for plants, scientific writing on the process of natural selection, and garden designs and planting plans; her most recent work makes use of maps both of the moon and the wider galaxy too.

Turnbull does not create beauty ex nihilo, but through the skill she employs in the process of transforming these source objects into art objects. In each case there is a tension between the desire to remain respectful to the source material and, at the same time, the need to pay due regard to the demands of the materials used. Turnbull's work reveals meticulous care in the application of paint to canvas; it is the precision of the artist's labour that allows the latent beauty of the source material to become evident in her paintings.

...

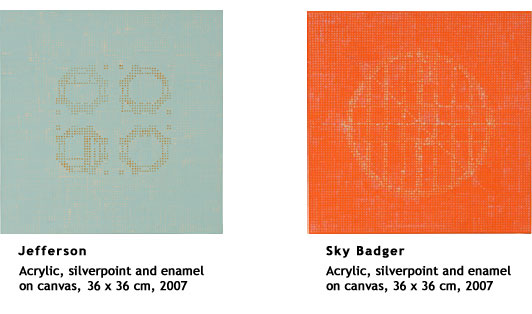

Consider two more pictures, smaller and more intense in colour. In one case the canvas is painted a shade of turquoise, reminiscent of oxidised copper, in the other case a shade of bright orange. The painted canvas is marked lightly with rows and columns of lines to establish a uniformly sized grid. At each intersection a dot of colour is delicately painted, creating the illusion of a coloured veil floating above the canvas through which the strong, evenly painted canvas colour is visible.

In the turquoise picture, darker dots form four circular objects that comprise what appears to be the base image and lighter dots form what appears to be a veil above them. In the orange picture it is the lighter dots that pick out the base image and the darker dots that rise from the canvas below. In each case the dots - regimented in rows and columns and in two colours - generate a pair of contrasts for the viewer: solidity and lightness, elevation and depth.

These pictures are named after built structures. They are representations of plans of structures designed to house sophisticated optical tools that facilitate the expansion of human knowledge, both of the galaxy in which our own planet orbits and of galaxies beyond.

The first picture is derived from the plans for a space observatory designed by Thomas Jefferson to be built in West Virginia after he had retired as President of the United States; the second picture is derived from the plans for the base of a modern telescope, built by a contemporary amateur astronomer whose nom de plume is Sky Badger.

These names remind us - elliptically - of places where men and women have sat and searched for stars: points of light in the sky, which some of the ancients' believed to be embedded in the inner surface of the veiled dome that encircled the earth. Astronomy has always involved a search for meaning as well as a search for knowledge. The early astronomers were philosophers as well as scientists, interested in facts but also in what these facts signified.

Beyond the intrinsic interest of the source material the artist achieves a different quality of interest. It is the form of representation that attracts and retains our attention as viewers. The content of the representation is not lost, but becomes subsidiary to the form. For the viewer what matters is how the picture looks not what the picture's source material means.

The vivid colours of the canvas; the subtle suggestions of form and depth provided by the grids of dots; the precision and delicacy of the paint marks: in Alison Turnbull's hands the facts have not ceased to be interesting but, more importantly, they have become beautiful.

|