Capital without Borders

by Brooke Harrington

(Harvard University Press, 2016)

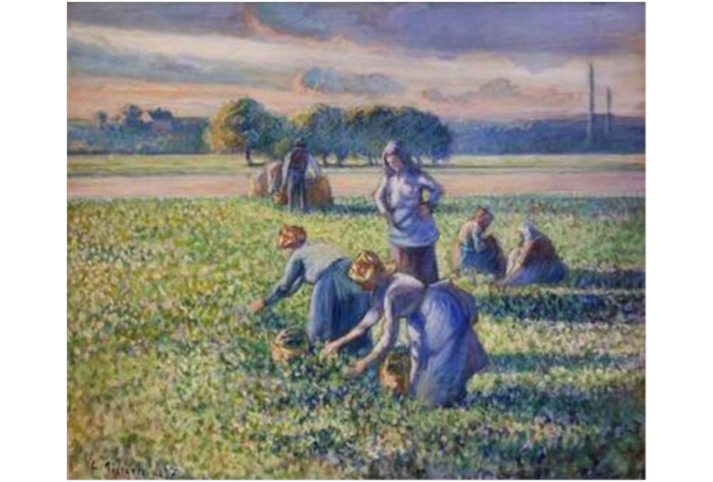

In 2017, two US art collectors loaned a painting, which they had bought at auction in New York in 1995, to the Marmottan Museum in Paris. When La Cueillette des Pois [Picking Peas] was displayed by the Marmottan as part of a retrospective of Camille Pissarro's work, it was recognised by Jean-Jacques Bauer as one of the many paintings confiscated from his grandfather by the French government in 1943. Relying on an ordinance, issued in 1945 in the immediate aftermath of the liberation of France, which repudiated the actions of the Vichy regime (declaring, "the nullity of the acts of spoliation carried out by the enemy or under his control"), Bauer applied successfully to have the painting returned to his family. Accepting that the US collectors had bought the painting in good faith, the French courts nonetheless supported the claim that the painting should now be returned to Simon Bauer's descendants as the rightful owners.

Camille Pissarro, La Cueillette des Pois, 1887. Camille Pissarro, La Cueillette des Pois, 1887.

Picking Peas is therefore a twice-confiscated painting: first, by a wartime government, beholden to an occupying foreign power with a track record of theft and spoliation and, secondly, by a democratically constituted government and a leading advocate for contemporary Europe's system of legal rights and obligations. Today, the restitution of art, looted from wealthy Jewish families by the Nazi's and their surrogates, is widely recognised as a triumph of legal legitimacy over Realpolitik. Like slavery, behaviour that was once considered acceptable and protected by formal legal powers, is now considered illegitimate and grounds for reparation.

This story poses a tricky problem for us. Positive law changes all the time, as societies add to, or amend existing laws, better to reflect changing beliefs, interests and practices. In addition, more general legal principles both the process by which laws are made and the general guidelines by which particular laws are judged acceptable also change. Not only might an act (or omission) that was legal at one time become illegal at another time, but the reasons why the legal status of the act (or omission) has changed, might themselves vary over time. Further, we know that there are no enduring historical benchmarks for what counts as socially legitimate. We might believe that we occupy the moral high ground, when we consider the behaviour of our forebears, but later generations will judge the social legitimacy of our practices by standards different from our own. Since legality and legitimacy are historically contingent constructions, even those of us who respect both the law and the spirit of the law in our own time, might not escape condemnation in the future.

*** ***

In Capital Without Borders, Brooke Harrington argues that the wealth management industry "radically undermines the economic basis and legal authority of the modern tax state" (p.17). Her book is unusual in its subject matter, innovative in its methodology, and generally persuasive in its argument: it is an important contribution to our understanding of the significance of the offshore financial services sector and the current limitations of cross-border financial regulation. Nonetheless, as I read the book, I found it impossible to supress the worry that encouraging governments and voters to regard the confiscation of the assets of the internationally-mobile rich as a desirable public policy goal, might well be viewed harshly by later generations who, with the benefit of hindsight, might not consider high levels of wealth and inheritance tax to be the most effective- and therefore, most legitimate mechanism for the promotion of social well-being.

Wealth management is often thought of as an industry dominated by clever young men, in a hurry to enrich themselves by means of further enriching their clients. There is an element of truth is this caricature, especially in some parts of the hedge fund sector. But the original and, in many ways the dominant contemporary ethos of the industry is the preservation of existing wealth rather than the creation of new wealth. For many, perhaps most clients, keeping what they already have is as important as acquiring more. Further, many clients desire to keep their wealth secret how much, where located, how invested to avoid the jealously of the public and the curiosity of the tax authorities. The wealth management industry's principal selling point - to the largest and longest enduring segment of its clientele - is its ability to preserve anonymity as well as value.

Today, the biggest threat to dynastic wealth that is, the ability of the rich to pass on their money and all the social advantages it confers, to their children and their children's children is no longer theft or destruction by jealous neighbours and rivals, but confiscation by government, eager for resources to fund redistributive programmes. Taking assets from the rich is a highly popular public policy, in both authoritarian regimes and in representative democracies. By contrast, Harrington says, the raison d'κtre of the wealth management industry has always been: "preserving the concentration of assets and socioeconomic status of an elite seeking to assert their autonomy from governance institution" (p.43).

The wealth management industry is a profession comprised of fiduciaries who act in trust to secure the financial (and other) goals of their clients that is itself assembled from a range of other professionals: lawyers, accountants, tax specialists and bankers. It constitutes an epistemic community, that is, a diverse group of specialists who share a common language, familiarity with a common set of skills and technologies, and a common set of values. In order to understand the profession how it works, how it reproduces itself, how it protects its reputation, how it advocates its value to clients Harrington spent two years studying on a wealth management training programme that qualified her to enter the profession as a practitioner, had she wished to do so. Instead, she used her knowledge and contacts to set up a series of sixty-five interviews with professional wealth managers, spread over eighteen countries, including most of the leading offshore financial centres, between 2008 and 2015.

The material from these interviews provides the most valuable element of the book, owing to the candour with which Harrington's interlocutors discuss their work and their clients: not in the sense of trading gossip or secrets about the rich and famous, but rather, having been granted a promise of anonymity for themselves and their clients, her interviewees supply an extensive range of revealing comments about how wealth managers balance their twin responsibilities to serve the clients' interests however these are articulated while also abiding by laws, regulations and professional codes of conduct. Finding means that are both legal and efficient, by which to achieve the clients' diverse goals, is the central professional challenge. Success at this task is well-rewarded: specific fee levels are never mentioned, but the costs of the best wealth management services are like the costs of haute couture clearly to be found on a different scale from the costs of more quotidian financial services.

The key to success in wealth management is trustworthiness, therefore an aspiring wealth manager needs to be able to signal their trustworthiness to clients in a convincing manner. As Harrington observes, "Like all professions, wealth management requires simultaneous mastery of both a body of expert knowledge and a set of context-specific 'mannerisms, attitudes and society rituals'

That is why, as Bourdieu explained, many professions 'set such store on the seemingly most insignificant details of dress, bearing, physical and verbal manners" (p.93). For the clients, the establishment and maintenance of trust is more important than the optimisation of economic value: their goal is not to maximise returns on assets, but to minimise the dissipation of existing wealth.

Who are the clients? They are a diverse group, whose only common characteristic is that they are very rich. Some have held wealth for many generations, some are the first in their families to acquire wealth; some are small, tightknit families with shared values and business interest, others are large, loosely connected and bound together only by the desire to keep their wealth to themselves; they like to hold assets offshore, some because the politics of their home nations are chaotic, and their wealth is vulnerable to confiscation by theft, others because the politics of their home nations are predictable and their wealth is vulnerable to confiscation by the tax system. Despite the diversity, all these families desire to keep their wealth out of sight and out of reach. Their biggest risks, therefore, are not stock-market crashes or credit-freezes, but transparency of ownership, the tax demands of governments and the follies of irresponsible family members.

The wealth management industry's principal tactic is to exploit the gaps in the international regulatory system: "each asset should be placed in the jurisdiction most favorable to the client's interests, whether that be minimizing taxes or defeating the claims of creditors and heirs

Second, the assets must be dispersed as widely as possible, in as complex a structure as possible; this makes the full extent of a client's wealth, as well as its true ownership, very difficult to assess" (p.135). As Harrington makes clear, what works to the benefit of clients works to the detriment of the tax gathering ambitions of onshore governments. The very rich are able to keep much of their wealth - and their privileges - and governments are forced to shift the cost of social programmes to those who are less rich and less able to avoid tax. The lack of transparency around ownership that the wealth management industry constructs via trusts, foundations and nominee companies, creates opportunities not just for the rich to lower their tax bills but also for the corrupt and the criminal to launder stolen money into the mainstream financial system. Which suggests that there are very good reasons to think that the industry should be much more effectively regulated. How can this be achieved? Harrington concludes her book by suggesting that, "political leaders interested in seeing elites pay their fair share of tax and otherwise submit to the rule of law should shift their attention away from wealthy individuals and onto the professionals who serve them" (p.303).

*** ***

The case for greater transparency around the ownership of asset holdings seems unarguable. Without clarity about the ultimate ownership of wealth, it is not possible to judge whether or not the tax system is fair and effective. In addition, opaque financial entities make it much easier for criminals to "launder" the proceeds of illicit activity into the mainstream financial system. Maintaining confidence in our fiscal and judicial processes requires greater openness, for which reason onshore governments have a strong interest in collective action to insist upon it. It does not follow, however, that the offshore financial centres where much of the wealth management industry operates must be "put out of business", as some campaigners have argued. Knowing who owns what - and how they came by it - does not of itself create a rationale for higher tax rates, or for tax harmonisation across onshore and offshore domiciles. They might be good reasons to allow small island nations the option to create low-tax economies, based around financial services, as a strategy to create well remunerated employment for their citizens, as an alternative to small-scale cash-crop farming and low-wage tourism.

Making the case for higher levels of taxation of income, of assets, or of bequests requires additional work, both with regard to the justification of particular levels of tax and the evaluation of the impact of redistributive spending. We cannot take for granted the neutral role of the state, given recent experience: states are often highly partial in the way in which they confiscate and gift assets, and future generations might find this partiality socially illegitimate. If the main beneficiaries either directly, in terms of subsidy, or indirectly, through privileged access to services turn out not to be the poorest but the middle classes, then the argument in favour of punitive taxation looks much weaker than is generally thought. Those who argue for more progressive taxation "Robin Hood taxes" - need to show not just that they are taking from the rich, but also that they are truly benefitting the poor; which is not self-evident in contemporary Western societies. Intelligent public policy needs to demonstrate the economic and social effectiveness of redistribution, rather than simply assume its legitimacy because of its supposed contribution to equality.

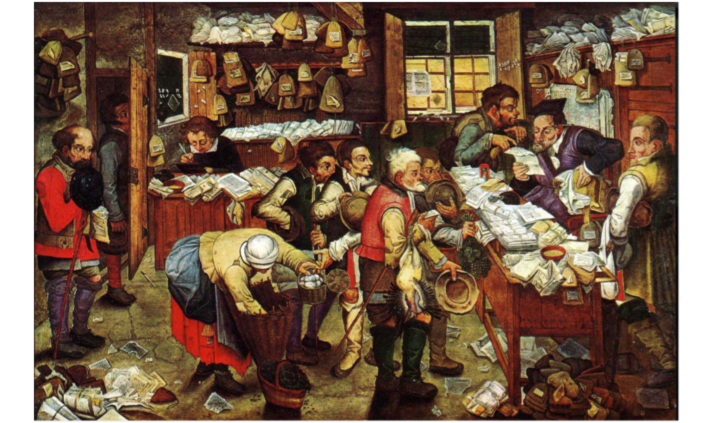

Pieter Breughel, The Tax Collector's Office, 1620-40 Pieter Breughel, The Tax Collector's Office, 1620-40

When Jean-Jacques Bauer reclaimed his grand-father's painting he was recovering property that had been taken from his family by the anti-Semitic Vichy government. But the French court that upheld his claim, also confiscated the painting from wealthy Jewish art collectors, Bruce and Robbi Toll, who have served as patrons to the Holocaust Museums in Washington and Tel Aviv, and as trustees of the National Museum of American Jewish History. The story of the ownership of Pissarro's picture reveals a deeply unpleasant feature or recent European history, namely that successful and wealthy Jewish families have been made to pay twice-over for the greed and prejudice of mid-century French and German nationalists. In each case, the confiscation of the painting was justified by the prevailing legal and social norms. It is not clear that future generations will regard the second act of appropriation as more morally justified than the first, even though many of us might think so now.

To assure ourselves that the confiscation of other people's wealth by means of positive law and regulation is more than a simple act of greed, we need not just to understand the way in which assets are hidden away by the wealth management industry, but also to demonstrate the justice of the redistributive social programmes that we wish to fund through more effective taxes on the rich. How we give determines the social legitimacy of how we take.

|