Looking at Warhol's Flowers

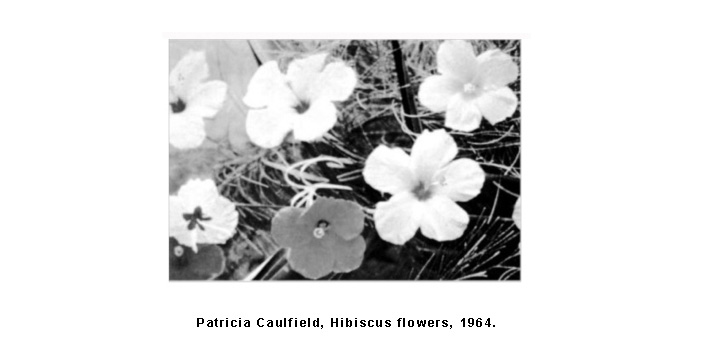

When Andy Warhol first showed his Flower paintings in November 1964, the critics were unsure what type of flowers he had painted: anemones said one, nasturtiums another, pansies a third. In fact they were hibiscus flowers, disguised by the process of transformation from flower to photograph to silkscreen painting.

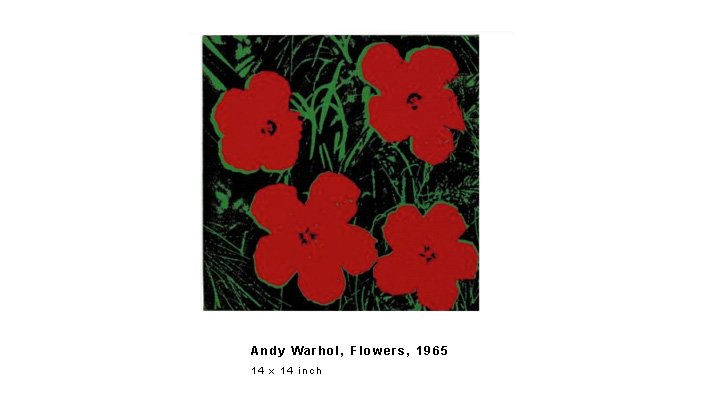

The original photograph - published in Modern Photography in June 1964 - showed seven hibiscus blooms. Warhol cropped and edited the photo, then had it copied repeatedly, on a photocopier, to create a square image with a flat, featureless bloom in each quadrant. The image was now ready for Warhol's silk-screen process, in which vibrant colour was applied in a variety of combinations, to produce a series of paintings, all of which shared a common basic structure but differed in the details.

The immediate and obvious variation was produced by changes to the colour of the flower petals, and in some cases to the background. Other variations were created by the rotation or inversion of the image. Further variations were the result of the deliberately sloppy technique by which the silkscreen ink was applied, in some cases leaving sections of the linen unpainted, in other cases allowing the colour to leach beyond the hibiscus petals and onto the background detail.

The serial repetition of an image, experimenting with minor adjustments to the position and the colour of the objects portrayed in order to affect the viewer's experience of the painting, pre-dates Warhol's work: Claude Monet's haystacks and Giorgio Morandi's vases are precedents. Nevertheless, it is characteristic of Warhol's work that he presented familiar objects over and over again - sometimes singular, sometimes in pairs, sometimes in fours, sometimes in larger multiples - with both subtle and dramatic variations of colour combinations.

Although Warhol's subject matter varied - he painted many different serial repetitions - but in each case the function of the object remained the same: to be a vehicle for his experimentation with colour. Warhol's Flower paintings are closer in spirit to Josef Albers' squares than Georgia O'Keefe's flowers: it's the colours not the flowers that matter. As Donald Judd observed in 1962, "The best thing about Warhol's work is the color".

This does not mean that Warhol's choice of objects was entirely arbitrary. Flowers have long been a central element in the vanitas painting and the still life tradition that dates back to Greek and Roman art . Just as fruit or fish will rot, so too, despite their fleeting brilliance, flowers are subject to corruption and decay. Their beauty is transient; as we look at them we know that they will fade and die. Warhol had already painted images of Marilyn Monroe (who committed suicide in 1962), of people jumping to their death from tall buildings, of car crashes, of an electric chair and of an atomic explosion.

Warhol's flowers are flush with colour and laden with symbolic value, but they are also images of images. He did not paint objects in the world, he painted media representations of objects in the world. Since his sources were photographs he was not distracted by the need to provide perspective or depth: the flatness of his paintings are "true to life". Warhol's painting is all about the surface.

To look at Warhol's Flower paintings is to look at colour. They remind us of our mortality, as still life painting should. They also remind us of the banality of reproduction and repetition, which is pervasive in the modern world, especially within the modern media. Yet, owing to the strength and vibrancy of the colour, they also remind us that our fragile world can be beautiful. They are memento mori but in glorious Technicolor.

References

- Heiner Bastian, "Rituals of Unfulfillable Individuality - The Whereabouts of Emotions", in Heiner Bastian {ed.}, Andy Warhol: Retrospective, Tate Publishing, 2001.

- Paul Bergin, "Andy Warhol: The Artist as Machine", in Art Journal, vol.26, no.4, pp.359-363, 1967.

- Norman Bryson, Looking at the Overlooked: Four Essays on Still Life Painting, Reaktion Books, 1990.

- Jennifer Dyer, "The Metaphysics of the Mundane: Understanding Andy Warhol's Serial Imagery", in Artibus et Historiae, vol.25, no.49, pp.33-47, 2004.

- Rachel Lane Hooper, "The Beauties: Repetition in Andy Warhol's Paintings and Plato's Ascent to Beauty", in The Legacy of Antiquity: New Perspectives in the Reception of the Classical World, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, December 2013.

- Michael Lobel, Andy Warhol: Flowers, Eykyn Maclean LP, 2012.

- Paul Mattick, "The Andy Warhol of Philosophy and the Philosophy of Andy Warhol", in Critical Inquiry, 24, 4, 1998.

- CÚcile Whiting, "Andy Warhol, the Public Star and the Private Self", in Oxford Art Journal, vol.10, no.2, pp.58-75, 1987.

|