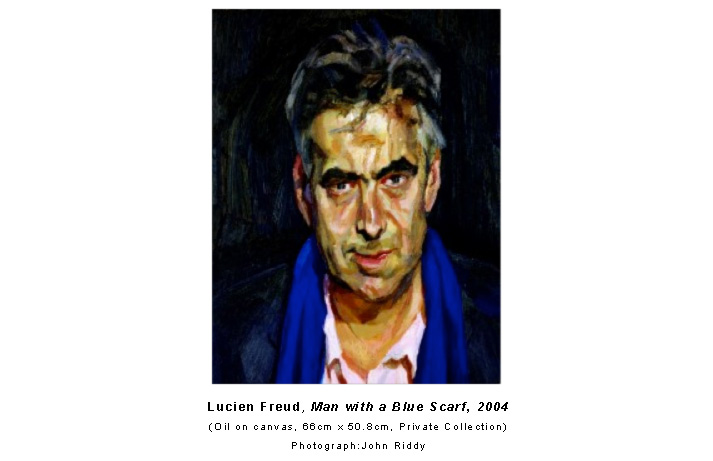

Man with a Blue Scarf

by Martin Gayford

Over a seven month period, during 2003-2004, Lucian Freud painted a portrait of Martin Gayford. Subsequently, Martin Gayford wrote a portrait of Lucian Freud painting Martin Gayford. There is a pleasing symmetry about these twin creative acts and, at the same time, a curious inequality.

Partly this concerns the inequality in status of the two men. Freud was an old man (over 80 when the painting was made) with a long and distinguished career and a strong critical reputation for his painting. Gayford by contrast is younger and less famous. While his books and journalism are well regarded, he has not yet attained a comparable standing in art criticism to Freud's standing in painting.

There is also the inequality of the artistic media. Painting and writing have different traditions, constraints and audiences. I have read Martin Gayford's book, Man in a Blue Scarf (Thames and Hudson, 2010) because multiple copies were printed and were available for purchase at less than £20 each. I have not seen Lucian Freud's painting Man in a Blue Scarf (2004), which is a unique object, because it hangs in its owners' house in California. Even had I wished to, I could not afford to buy it. Consequently, I am writing about a book about the making of a painting; I am not writing about the painting itself (which is reproduced below).

Wanting to have one's picture painted requires a blend of opportunity, curiosity and vanity. The process requires access to an artist of suitable quality and then plenty of time and patience as the work progresses. The sitter is ideally placed to watch the artist at work and to question them about their aims and technique, as the portrait emerges ready for display to friends and family, and for preservation for posterity. Regardless of whether the picture is judged a good likeness, the very existence of a painted portrait suggests that the sitter believed in their own importance (in a way that a photograph does not).

In his recent novel, By Nightfall (Fourth Estate, 2010), Michael Cunningham describes the moment of self-realisation when his main character faces up to the lack of significance of his life. As befits a middle-aged art dealer he considers his fate in terms of a portrait:

....Peter, a small figure on an undistinguished corner of Manhattan, will have to forgive himself, he'll have to grind himself down because it seems no one is going to do it for him. There are no gold-leaf stars painted in lapis over his head, just the gray of an unseasonably cool April afternoon. No one would do him in bronze. He, like all the multitudes who are not remembered, is waiting politely for a train that in all likelihood is never going to come. (p.221).

Martin Gayford was more fortunate: when he suggested to his friend, Lucian Freud, that he would be interested in sitting for a portrait, Freud's immediate response was, "Could you manage an evening next week?" (p.9).

Gayford's book takes the form of a series of diary entries, starting in late November 2003 and ending in early July 2004. (There is a short addendum, covering the period from August 2004 to April 2005, when Freud makes an etching of Gayford; and a postscript from June 2005 when both painting and etching were displayed at a museum in Venice). From the outset it becomes clear that writing about being painted is difficult. There are some delightful descriptions of Freud moving around his studio, selecting brushes, mixing pigments, adjusting the easel, and moving from foot to foot as he looks, thinks, paints, then looks some more, thinks some more and finally paints some more. Fascinating though these passages are, there is only so much one can write about the physical activity involved in the painting of a picture, not least because, as Michelangelo said, "A man paints with his brains and not with his hands".

It is appropriate, then, that much of Gayford's book takes the form of recorded conversations between the artist and the sitter, either during breaks in the painting process, or at dinner afterwards. The book turns out to be a summary of Freud's thoughts on various interesting topics rather than a detailed technical description of Freud's process in making a painting. Freud himself has not written much. He says, "Writing is so enormously hard that I can't understand how anyone can be a writer" (p.54). So a book of conversations that offers the reader access to his reflections on his own working practice and output, and on the work of other artists, is a valuable thing, not least because of Freud's recent death, at the age of eighty-eight, in July 2011.

While Freud found writing hard he clearly loved to paint and did so for many hours, on most days during his long life. What emerges from Gayford's account is the degree of concentration that Freud brought to his work: "The only secret ....I can claim to have is concentration; and that's something that can't be taught" (p.208). Even as an old man he brought tremendous focus, energy and discipline to his work. Freud recounts a revealing anecdote about Caspar John, who was the second son of Augustus John (1878-1961) the leading British portrait painter of his day. Caspar joined the navy as a young man and ended his naval career as an Admiral and First Sea Lord. Once, when asked about the contrast between the rigours of military life and the bohemianism of his father's life as an artist, he replied. "To be a painter requires enormous discipline"(p.130).

Freud combined his disciplined practice in the studio with a healthy appetite for the bohemian lifestyle outside of it. Many of the memorable conversations in the book are recorded as having taken place in taxi rides from the studio to one or other of London's leading restaurants, or over dinner itself. Further, Freud's conversation is full of stories of his famous friends and his enjoyment of their company. The only time I ever saw him, he was having lunch at Sally Clarke's in Kensington Church Street. His guest that day was Kate Moss, for whom lunch appeared to consist of a plate of green salad and a cigarette. It turned out that he was painting her portrait at the time.

Kate Moss provides the link to what is, for me, one of the funniest moments in the book. Freud attends her thirtieth birthday party where he meets Damien Hirst. On hearing this the following day, Gayford mentions a remark that Hirst has made to him about Freud's work:

What I love about Freud is that interplay between the representational and the abstract. His work looks so photographic from far away; and when you get up close it's like an early de Kooning. You can tell a great painting because when you get close there are all these nervous marks.

Freud is apparently pleased with this and responds by reporting on comments made to him by his working class neighbours in Paddington, where he lived in the 1940s.

Lu, your work is funny. When you look at it from a distance you can see what it is, but when you look at it close to, it's a complete mess. (p.96).

Stripped of its technical language Hirst's remark is indistinguishable from that of the neighbour with no knowledge of art at all.

Is there nothing substantial that separates the aesthetic judgements of the ordinary person from the art expert? Perhaps the latter merely disguise the prosaic nature of their opinions by the use of more complex language? What remains ambiguous is whether Freud wanted to suggest this idea, by replying in the way he did; or whether Gayford wanted to suggest it by reporting the comments in the way he did. Either way, the thought that much contemporary art commentary is merely common sense plus name-dropping would probably have appealed to Freud who, as the book makes clear, read widely and thoughtfully.

What really takes place in the process of making a portrait? Near the end of the book, once the painting is completed, Gayford considers this question:

Man with a Blue Scarf is in part, I think, a painting of my own fascination with the whole process of being painted. I see that intensity of interest in the picture. It's me looking at him looking at me. But as good pictures can be more than one thing at the same time, it also has a certain look of LF. (p.216).

There are two distinct ideas here, both of which concern the relationship between the painter and the painted: first, that what a portrait shows is the image of the sitter at a moment when the sitter is looking at the painter. Second, that a portrait tells us something not just about the person who is being painted but also about the person who is painting.

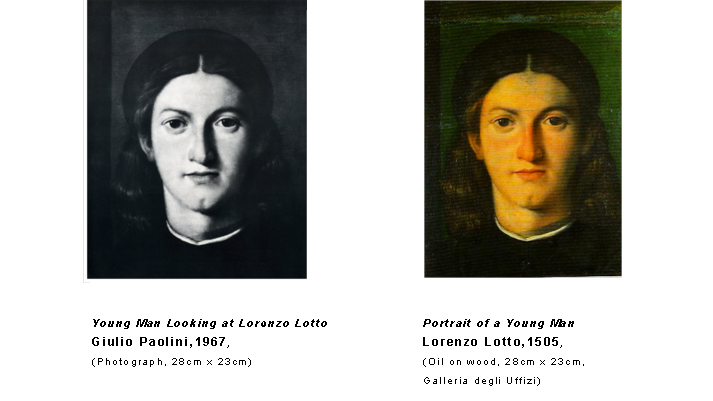

The inevitable narcissism in the relationship between painter and painted is a theme in the work of the artist Giulio Paolini (b. 1940). In an exhibition in 1967 he displayed an actual-sized photographic reproduction of Lorenzo Lotto's painting, Portrait of a Young Man, which was made in 1505. Paolini entitled his photograph, Young Man Looking at Lorenzo Lotto, making the point that just as Lotto was looking at the young man whom he was painting, so the young man was looking at Lotto while he was painting. A portrait is a picture of someone watching an artist painting their picture.

Paolini said of this work that he wanted to re-create the moment in which the painting was made, to transform the viewer into the painter. The visitor to the Uffizi might think they are looking at a picture made half a millennium ago, but Paolini wanted them also to imagine that they were Lorenzo Lotto, being watched by the young man as the picture was made.

While the painting, Man in a Blue Scarf shows Gayford looking at Freud while Freud paints Gayford, so the book Man in a Blue Scarf shows Freud painting a portrait of Gayford while Gayford observes Freud in the act of painting. What is written is in part what Freud reveals to Gayford, just as what is painted is in part what Gayford reveals to Freud. Observation, in these cases, is a two-way process. It is not always clear who is the subject and whom the object.

This ambiguity is deepened when we consider that the making of a portrait, in words or in paint, is always to some extent the making of a self-portrait. Man in a Blue Scarf is evidently a painting of Martin Gayford; but it is also evidently a painting by Lucian Freud. I assume that the owners of the painting bought it primarily because it was by Freud and not because it was of Gayford. In the book Gayford quotes a remark of Paul Gauguin, "Pictures and writings are portraits of their authors" (p.216). This thought has been expressed by writers too. In an essay on the Francis Bacon, written in 1995 and published in the collection Encounter (Faber Faber, 2010), Milan Kundera writes,

When one artist talks about another, he is always talking (indirectly, in a roundabout way) of himself, and that is what's valuable in his judgement. (p.8).

The skill that the artist, whether painter or writer, brings to their work might help to reveal otherwise obscure qualities in the objects they depict. At the same time these skills reflect something of the character of the artist themselves. If we see Gayford in a new light because of Freud's painting, it is because Freud turned that light upon him. If we see Freud in a new light because of Gayford's book, it is because Gayford turned that light upon him.

In her book on self-portraiture, A Face to the World (Harper Press, 2009), Laura Cumming writes that,

....paintings are fictions, and self-portraits too; there is not a novelist alive who does not believe it possible to enter the mind and voice of someone else, real or imaginary, and the same is true of painters. (p.93).

Freud himself is reported by Gayford to have said,

I would wish my portraits to be of the people, not like them. Not having a look of the sitter, being them. I didn't want to get just a likeness like a mimic, but to portray them, like an actor. (p.112).

It is this capacity to 'give life' to a person or character - the achievement of verisimilitude - that transforms the dabs of oil on canvas and the rows of inky marks on paper, into a work of art. For the viewer or reader, the phenomenological magic of great art is that we become convinced that we are actually there, as an observer, in the painting or in the story; while, at the same time, we also know, full-well, that we are merely standing in a gallery looking, or sitting in an arm-chair reading. For this magic to work - to have the illusion of 'being there' while simultaneously 'being here' - the painting or writing must convince. This, in turn, requires a certain predisposition on the part of the viewer or reader to be convinced.

These reflections on the process of making art do not, however, explain why some art is generally thought to be better than other art. If all art is a form of self-portraiture - and all writing a form of autobiography - why do we think that some artworks - or books - are better than others? Freud, as this book reveals, had some trenchant views of his own on the merits of work by other artists. So, when Gayford writes that "I have long been convinced that Lucian Freud is the real thing: a truly great painter living among us" (p.7), he must mean something more than that a portrait by Freud is always also in some ways a portrait of Freud. He must also mean, I think, that for something to be a portrait by Freud is a very good thing to be.

It is not the subject of the painting nor the identity of the painter that determine the aesthetic quality of the work. Rather it is the content of the work that is decisive: by which I mean both what the painter puts in to the work and what they choose to leave out. Content, in this sense, includes both the elements that make up the work and the style with which these elements are included. Content is both what we see and how we see what we see. The subject of Lorenzo Lotto's Portrait of a Young Man and the subject of Giulio Paolini's Young Man Looking at Lorenzo Lotto are the same, but the content is not. It is the content that provides the basis for the judgement that the former is a great painting while the latter is merely an interesting photograph.

The portrait of Lucian Freud that emerges from Man in a Blue Scarf is of a man who had thought hard and worked hard for many years to establish his reputation, through a large and distinctive body of work. His vision is characterised by an unflinching attention to detail and an honesty (to the point of ruthlessness in some cases) about his subjects. He was pre-occupied with importance of capturing the physicality of his sitters: the precise colour of their flesh, their weight, the form their body took when at rest. He believed in the individuality of everything - not just people, but animals, plants, and inanimate objects - and wanted to record this uniqueness.

To understand just how well Freud succeeded in these goals would require a close examination of his paintings. Martin Gayford's book is the perfect appetizer for such a task: his portrayal of the painter at work makes one hungry to look once again - 'in the flesh' - at examples of the painter's work.

|